Since it’s still not the default to sketch out ideas, since verbal communication is our primary mode of working, a question that comes up frequently around visual note-taking is why is it worth it?

Why is it worth sketching out ideas rather than just writing them down or talking about them?

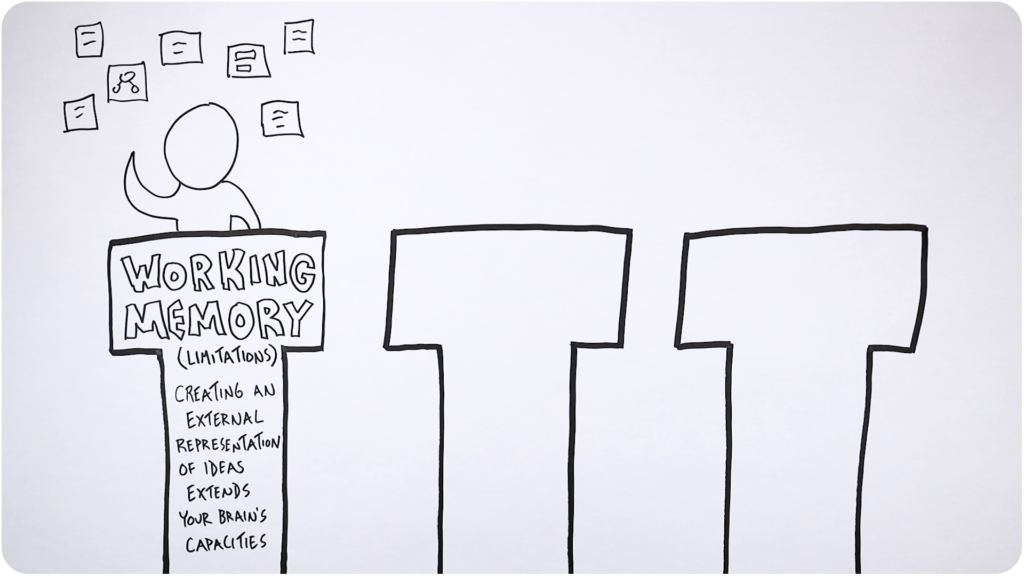

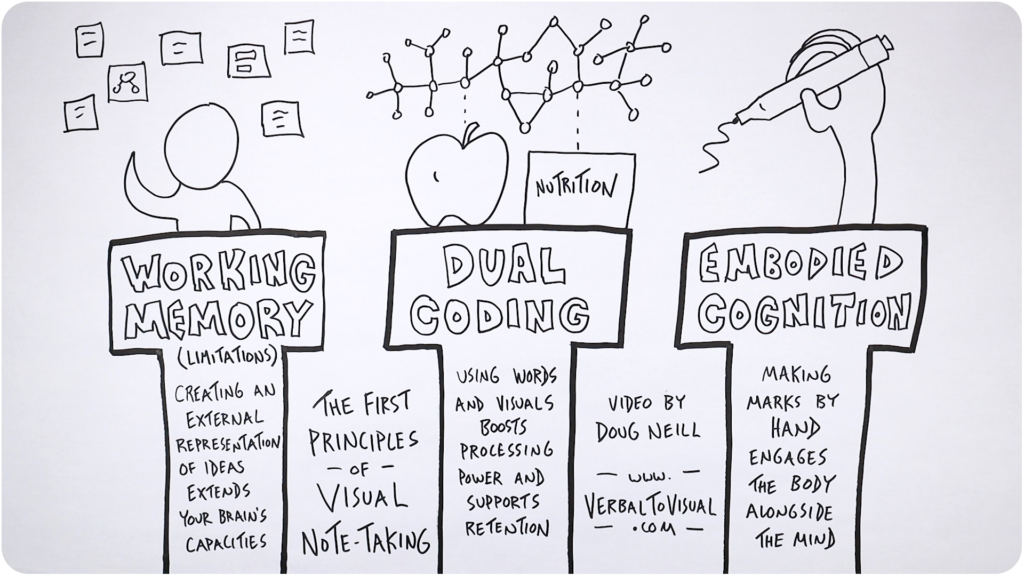

I’m going to attempt to answer that question by sharing what I see as the first principles of visual note-taking.

There are three of them, and I’m going to use a pillar analogy to capture them.

The Limitations of Working Memory

The first principle has to do with your working memory, and specifically the limitations of it.

The idea of working memory comes from cognitive load theory, which tells us that there are only a certain number of things that we can keep in mind, that we can be actively working with, at any given time. Depending on the complexity of that information, it’s anywhere from four to seven distinct pieces of information.

Visual note-taking is a tool that gets us past that limitation. By creating an external representation of ideas, you’re extending your brain’s capacities.

So if you’ve ever found it helpful to jot individual ideas down on sticky notes or index cards, place them on the desk in front of you, and then move them around to help understand how those ideas are connected to each other, what you’re doing is overcoming the limitations of your working memory by creating tangible artifacts. Your brain doesn’t have to keep track of each idea individually, but instead can focus on manipulating them to figure out how they’re related to each other and what you want to do next.

That’s true even if you’re not physically moving ideas around but simply capturing them all on one page. The marks give you a reference that helps you to work with more complex ideas without losing sense of the big picture.

So if you ever find yourself in a conversation where you’re continually running in circles, part of the reason is likely because you and whoever you’re chatting with are relying on your working memory to keep track of what’s going on. If you start to jot things down that you both can look at, that’s likely a step that will help you move forward with whatever it is you’re discussing.

The limitations of your working memory supports note-taking in general, whether or not it’s visual. The next two pillars will speak specifically to the visual nature of sketchnoting.

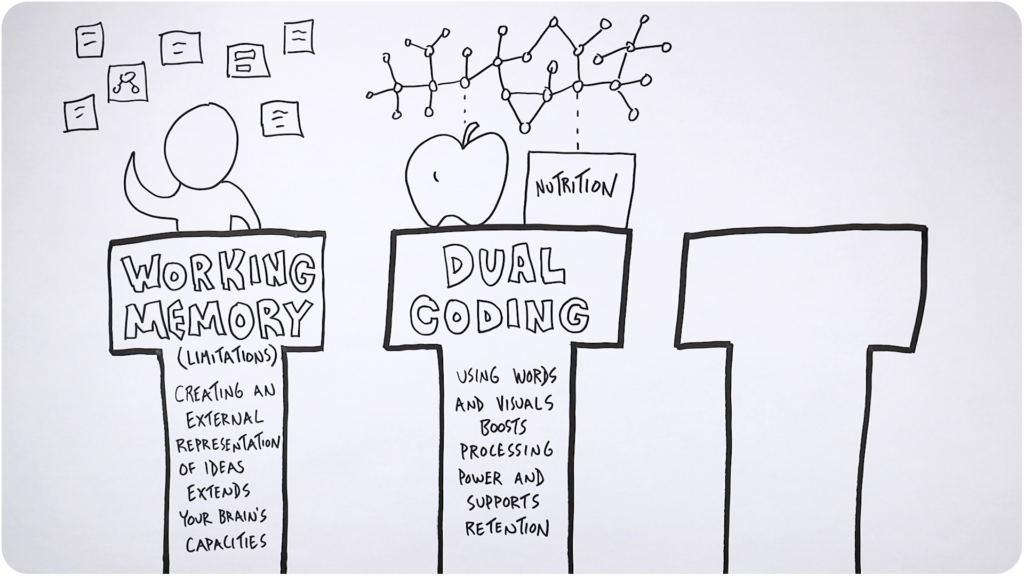

Dual Coding Theory

The middle pillar is dual coding theory. The dual refers to the combination of words and visuals, and how that combination boosts your brain’s processing power and supports retention.

To see how, let’s imagine the sketched image of an apple, and then the word nutrition.

That image of an apple will trigger a particular set of neurons in your brain, neurons related to your past experiences with apples, the degree to which you enjoy eating them, maybe the thought of a full apple tree or orchard, or even a memory of going with your family to a you-pick farm when you were eight years old.

Similarly, the word nutrition will also trigger a neural network within your brain. Maybe you’ll think about what you had for breakfast, maybe a new year’s resolution that you stuck to (or didn’t), and likely some specific foods that you consider to fit into that category of nutritional. That’s where you’ll start to see some overlap in the two networks.

What this overly simplified model is designed to represent is the link that is inherent in our brain because of the fact that we’re visual creatures, and how the inclusion of these two ways of thinking have two positive impacts.

It boosts our overall processing power because we’re tapping into a larger portion of our neural network, and it supports retention because of the new links that we make when we merge those networks together. We’re encoding new information in a deeper way when we include words and visuals.

What I appreciate about these implications of dual coding theory are the benefits of visual note-taking in the moment (from that processing power perspective), as well as the benefits after the fact because of the ways that this combination supports the retention of new ideas.

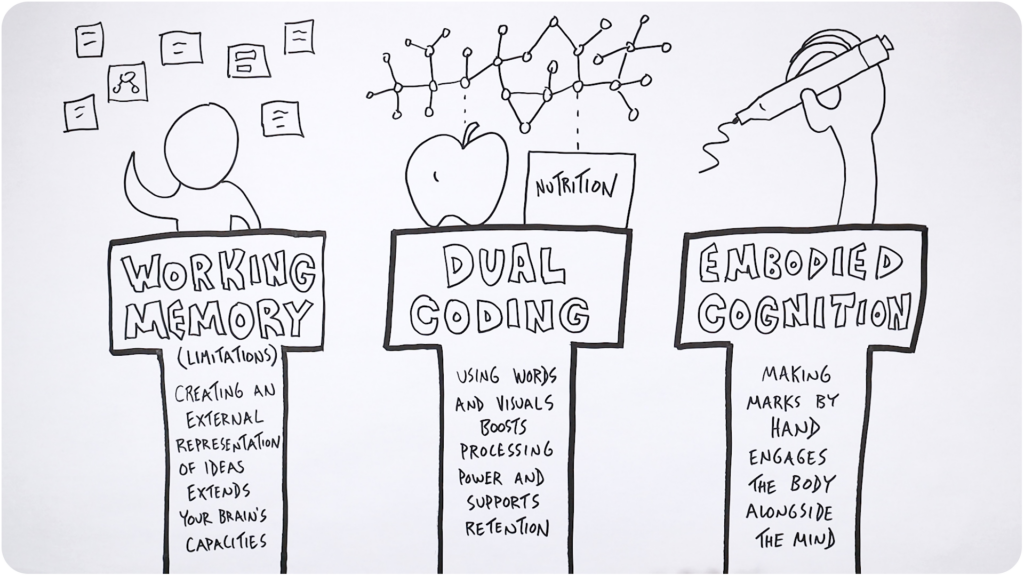

Embodied Cognition

Let’s next look at the third pillar, which is the idea of embodied cognition.

This theory approaches the entire working of our brain from the perspective that it exists not just up in our head, but throughout our physical body. It’s the opposite of a dualist approach which tries to split entirely the cognitive functions (your brain) and your body.

Embodied cognition approaches things from an integrated perspective and explores how the very working of our brain arises from the physical experiences that we have in the world, through our body.

As it relates to visual note-taking, it’s the making of marks by hand that engages the body in support of the mind. We’re using our physical body to make marks on a page while actively thinking through a particular set of ideas.

Embodied cognition is part of the reason I’ve enjoyed working at a larger scale lately. With big poster paper in front of me it’s easier for me to get more of my body involved in the process. I also enjoy making larger marks as opposed to tiny ones.

This is also related to the benefits of using something like sticky notes up on a wall. The physicality of being able to move those ideas around, step back, walk to this side and then that – those are all ways of using your body to gain new perspective on whatever it is you’re working on.

Another interesting implication (or even justification) for this concept of embodied cognition is the prevalence of metaphors within our language, and how the vast majority of the metaphors that we use arise from our experience as physical creatures in the world.

Take, for example, the idea of feeling up versus down. Up refers to happy, energized. Down refers to sad, dejected, tired. That corresponds to what our body is doing in those two different types of states.

Even the visual metaphor that I’ve chosen to use here, the concept of pillars, is related to our experience making things and our knowledge that the right type of supporting structure will keep the roof from falling down on us. That’s why we talk about people being pillars in our lives. In the case of these first principles, we’ve got conceptual pillars that support a particular way of working with ideas.

So in addition to visual note-taking tapping into the use of the physical body by making marks, it also allows for the sketching out of visual metaphors that have arisen naturally in language. We’re able to represent those visual metaphors that already make up a large part of how we think about and process the world.

From First Principles to a New Way of Working

These three pillars remind me why it’s worthwhile to work more visually with ideas.

They can also be a jumping off point for chatting with others about working in this way, whether you’re a teacher introducing these skills to your students, or you’re in the workplace and you want to get more people up at the whiteboard instead of staying stuck in circular conversations around the table.

My hope is that sharing these ideas can contribute to a broader shift toward the appreciation of working with sketched visuals. In the typical education experience, it’s around second or third grade when drawing is removed from the curriculum and we enter a phase of heavy dependence on verbal processing.

One of my goals with this website and the YouTube channel is to help shift things back in the visual direction a bit, to give people both the skills that are needed to work more visually as well as the justification for doing so.

So I hope that it has been helpful to see these first principles of visual note-taking sketched out in this way.

If the skill of visual note-taking is one that you would like to develop, come check out what’s going on inside of Verbal to Visual.

Over the years I’ve developed a set of online courses to help you build and use these skills in different ways. You’ll also find a global community of visual thinkers working in a variety of fields who are sharing their work.

And anytime you need a reminder of why it is that you’re starting to draw again as an adult, or what it is that this sketchnoting thing is all about, come back to these ideas. These pillars will remain strong supports, long into the future.

Thanks for spending some time exploring these ideas with me. I look forward to sharing more with you next time.

Till then,

-Doug